The Utah Drone Report 2016

The Utah Drone Report 2016

Economic, Legal, Social, and Technological Trends

By The Students of HONOR 3374 – Drones & Society || Fall 2016 || Honors College || University of Utah

Executive Summary

Unmanned aerial systems (UAS), commonly known as “drones,” are playing an increasingly important role in American society and economy. This report examines the emerging use of drones in the state of Utah in relation to larger, national drone trends. The report finds that many national trends are mirrored in Utah. This includes a rapidly expanding drone industry that includes a unique focus on filmmaking. But, like many other states, Utah faces challenges related to public perceptions of drones and the potential threats that they pose to safety and privacy. In response, Utah has passed legislation to address some of these concerns. Nonetheless, the state has sought to balance responses to these concerns with efforts to promote the growth of the drone industry in Utah.

Table of Contents

National Context

Politics & Law

Economics & Industry

Science & Technology

Society & Culture

Acknowledgements

National Context

Rachel Nelson, Avery Conner, Zak Bastiani, and Logon Rosson

Rarely has a technology had such a revolutionary impact on society within a short span of time as drones have had in the United States in recent years. While first developed for military use, the modern concept of drones has expanded to include commercial and recreational uses as well. Drones have since often emerged on the forefront of media around the world, both making news and covering it. In the United States, drones have become an increasingly large part of everyday life, specifically in the areas of politics and legislation, economics and business, and science and technology. In recent years, social and cultural values and attitudes toward drones and technology in general have shifted in response.

Political and Legal Context

As drone use has proliferated in the United States, safety and privacy concerns have prompted government response at all levels. Across the nation, state, county, and even city governments have put rules and regulations in place along with those enacted by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The result is a sometimes confusing conglomeration of requirements that may or may not be redundant or simply clash with rules already in place. As such, it is still important to know the laws that do concern drone use, both federal and local, and how they interact in order to ensure safe and fulfilling drone operations.

On August 29, 2016, the FAA enacted Part 107, also known as the Small UAS Rule. Part 107 does not address privacy, but instead focuses on safety while flying drones. Among other rules, the Small UAS Rule requires that drones weigh no greater than 55 pounds, must not carry hazardous material, and the operator must have a remote pilot airman certificate or be supervised by a person with a remote pilot certificate. However, Part 107 does not apply to model aircraft. As a result, for many Part 107 is not applicable, as “Congress defined a ‘model aircraft’” as any drone that “Is capable of sustained flight in the atmosphere…is flown within visual line-of-sight of the person operating it…[and] is flown for hobby or recreational purposes.” If an operator’s drone usage falls under this category, he or she need not worry about Part 107, but are instead regulated by Subpart E of Part 101.

On August 29, 2016, the FAA enacted Part 107, also known as the Small UAS Rule. Part 107 does not address privacy, but instead focuses on safety while flying drones. Among other rules, the Small UAS Rule requires that drones weigh no greater than 55 pounds, must not carry hazardous material, and the operator must have a remote pilot airman certificate or be supervised by a person with a remote pilot certificate. However, Part 107 does not apply to model aircraft. As a result, for many Part 107 is not applicable, as “Congress defined a ‘model aircraft’” as any drone that “Is capable of sustained flight in the atmosphere…is flown within visual line-of-sight of the person operating it…[and] is flown for hobby or recreational purposes.” If an operator’s drone usage falls under this category, he or she need not worry about Part 107, but are instead regulated by Subpart E of Part 101.

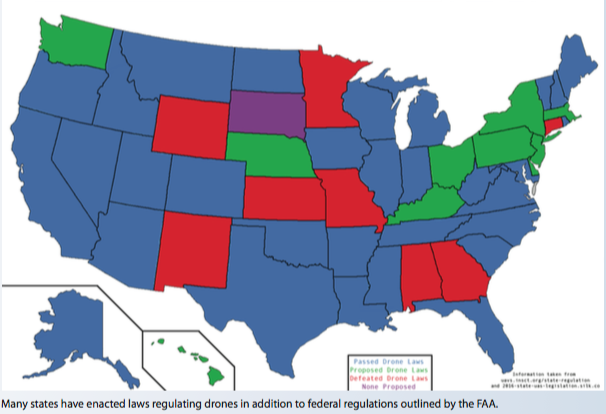

Either in response to privacy concerns or simply disappointed by the lack of response from the FAA, many local governments have proposed laws to address these concerns. Other issues addressed in proposed legislation have included prohibiting drones used for hunting and limiting law enforcement use. Currently, 32 states have passed laws that address issues with drones, and at least 40 cities have proposed or enacted their own laws. Legislators seeking to enact drone laws have found that proposed legislation is often redundant. For example, Connecticut has yet to enact any laws that specifically address drones, as it already has rules in place for aircraft and drones are currently considered aircraft by the FAA. The same is true for the District of Columbia. The airspace above Washington D.C. is the most restricted in the country, and drones are strictly prohibited, even without laws that specifically address them.

Drone regulation passed by federal and local governments has the possibility to create a significant problem when those regulations contradict. In many circumstances, local laws are more explicit and specific than federal laws. As a result, a drone operator easily could be obeying federal law while disobeying local law. The FAA itself has “issued a Fact Sheet asserting their ultimate authority over drone regulations.” The issue of whether or not it is lawful to be arrested for breaking a local law while obeying a federal law has yet to be decided, and states continue to propose new legislation that could contradict FAA guidelines. Additionally, each state enacting their own drone laws creates confusion across borders and slows innovation nationwide. States might have entirely different laws or different interpretations of similar laws, which could create additional problems for businesses seeking to utilize drone technology across state lines in the near future.

As drones have become more abundant and accessible to pilots ranging from business to hobby usage, governments at every level have responded by seeking to regulate them through legislation. Issues arise when laws at different levels conflict and the full extent of the FAA’s authority and role in regulating drones has not yet been confirmed. Even as these problems emerge, states and cities continue to make new regulations that might dissuade drone industries nationwide. These issues must be resolved in the near future as drones become more integrated into society and laws must become more congruent in the process in order to have a well functioning society.

Economics and Industry Context

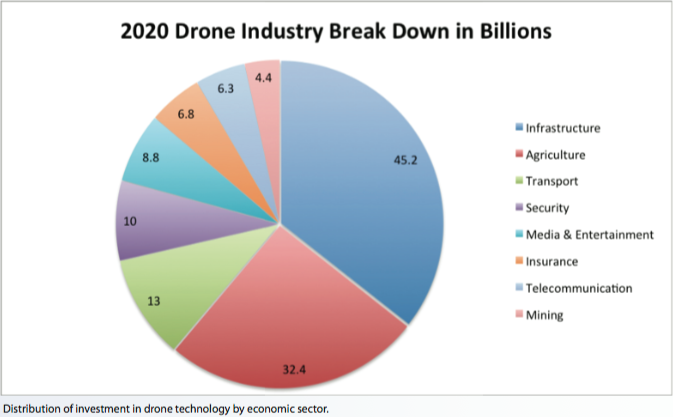

The rapidly-growing drone industry has had a significant impact on business within the United States and the world. The global drone industry is expected to reach 127 billion dollars by 2020 compared to its current value of 2 billion. This estimate has drastically changed from a 82 billion by 2025 that was predicted in 2013. Piotr Romanowski, a Price Waterhouse Cooper’s partner and an advisor leader, believes that this growth will be largely due to the the decreasing cost of drones. This exponential growth is not limited to any one area of the drone industry. Aerial photography’s worth is expected to grow to 2.8 billion dollars by 2022. The military drone industry as well is expected to grow, from the current 4.8 billion dollars to 6.8 billion by 2022. The market for drone transponders, the simplest parts that prevent in-air collisions, is projected to be worth 2.5 billion by 2022. The commercial drone market is expected to reach 2.05 billion by 2023 in North America.

GoPro, a company that has previously focused on their cameras for action sports, expects to capitalize on this market as the majority of drone use currently is for film and media. However, GoPro has yet to see significant gains from the highly competitive drone market. GoPro has already seen a 48% decrease in profit from 2015 to 2016. Additionally, the October 2016 recall of their Karma drone has set them further behind in the industry. Even Parrot, a company that’s main output is drones, has also felt the effects of the competitive drone market. For quarter three of 2016, they cut sales by 55 million euros, causing a 15 percent drop in stock value. However, DJI hasn’t been negatively affected by this competition and plans to further increase competition with the release of its newest drone, Mavic, in last 2016.

By some calculations, DJI currently controls 70% of the hobbyist market and many argue that the company has been hugely influential in affecting prices for drones by the sheer number of units is has on the market. In late 2016, DJI released its Phantom 4 and Inspire 2 onto the consumer market. As DJI continues to release new drones, they take profits away from their own previous models in a maneuver called cannibalization. While companies usually fail after releasing products in such a manner, analysts argue that this tactic has proven successful in the drone market by allowing companies, such as DJI, to firmly establish themselves in the market. Logan Campbell, founder of a drone consultant agency Aerotas, argues that “DJI is actually solidifying its place in the market rather than risking it.” Indeed, DJI has established its place at the forefront of the industry, as in 2015 alone, DJI made 1 billion dollars in revenue, which equates to nearly 50 percent of the worldwide drone market.

The U.S.-based startup 3D Robotics has encountered difficulties in breaking into the drone industry, largely due to the drone giant DJI. One major problem arises from the low selling price of DJI’s products. While DJI’s prices originate in the thousands, 1000-1500 for consumers, they eventually fall down by almost 50 percent. This makes it nearly impossible for other companies to find a place in consumer drone market. In response, 3D Robotics has shifted its focus to building drones for construction modeling. The company claims that their technology will allow for full 3D modeling of worksites as well as greater accuracy in measurements of volume, height, and length within the models. Due to the massive control that DJI has on the drone industry, companies are currently unable to directly combat them in the consumer market; instead companies are trying to maximize on smaller, specific markets in order to survive.

Science and Technology Context

Drone technology is both a result and catalyst of innovation. As technology is becoming smaller, lighter, and more powerful, drones are becoming more useful in a variety of scientific fields, ranging from geology to meteorology and atmospheric sciences to even agriculture. Dr. Karen Joyce, an environmental scientist, first saw the potential of using drones for science while working for the military, but, as she recalls, “They couldn’t understand why I would want to use [a camera that looked down at the ground instead of forward at a target]. But it sort of got me thinking…this would be quite a cool technology to try to bring access into research and the academic world.” Since then “scientists, like Dr. Joyce, are using drones for a diverse range of purposes such as mapping remote environments, monitoring agricultural crops, tracking wildlife, identifying biosecurity threats and distinguishing features in the landscape such as craters or erosion.”

In many fields of science, drones now allow researchers to gather data in ways that were not previously possible. Drones have made research cheaper, which thereby allows researchers to gather larger volumes of data. Dr. Joyce, for example, has used drones to hover over reefs and observe from a moderate height, rather than being forced to examine smaller areas or gather funds for helicopters to fly high above the reef. Drones have already had a similar impact on forest conservation efforts as well. Dr. Rakan Zahawi of the Organization for Tropical Studies states that “using drones to replace manual labor can reduce the costs associated with monitoring conservation projects. This could result in more people monitoring their land in the tropics, giving us better information about what works and what doesn’t.”

Scientists have also found that drones allow them access to areas that are inaccessible and potentially dangerous to human researchers. Earlier, wind farmers had been forced to rely on “mathematical formulas, wind tunnel tests and computer modeling to guide the placement of in dividual wind turbines.” In order to maximize efficiency, “there’s an urgent need for tools that can be used to make precise measurements and create accurate simulations of different wind turbine placements” and drones have the capacity to measure, rather than estimate, the necessary data. Researchers have found that the same holds true in their study of hurricanes. Drones are now used to “deploy sondes, probes that automatically transmit information about surroundings” and gather data that “assist[s] in predicting the intensity and path of current and future hurricanes.”

dividual wind turbines.” In order to maximize efficiency, “there’s an urgent need for tools that can be used to make precise measurements and create accurate simulations of different wind turbine placements” and drones have the capacity to measure, rather than estimate, the necessary data. Researchers have found that the same holds true in their study of hurricanes. Drones are now used to “deploy sondes, probes that automatically transmit information about surroundings” and gather data that “assist[s] in predicting the intensity and path of current and future hurricanes.”

Drones have had such an impact in some fields of science that they have changed the very nature of research. The Cambridge Archaeological Unit has utilized drone technology to “provide key surveying capabilities and point the way to new excavation sites,” according to Alison Dickens, manager of the group. Archaeologists now have the ability to combine information from the ground, such as writings from scholars, and aerial imaging to not only identify but also to document excavation sites.

Drone technology itself has developed in recent years. Besides the development of cameras and other imaging equipment, some hope that drones might soon be used to carry larger loads and have longer flight times with more powerful batteries. Drones become more useful in a myriad of capacities with the addition of new sensors and other equipment. At AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas, drones now carry “mobile signal measuring devices” that assess the strength of signals in each seating area, which then allows the company to make necessary adjustments. According to AT&T Drone Program Director Art Pregler, they fly drones in order to “understand what is going on at each seat in the stadium so we understand the user frustration.”

As scientists are integrating drones into their research, laws currently pose a significant obstacle to utilizing drones to the fullest extent. FAA laws currently regulate where operators may fly drones and many smaller agencies, such as city governments and the National Park Service, have begun enacting regulations that prohibit or limit drone use in areas of interest to many scientists.

Social and Cultural Context

In recent years, drone use has expanded rapidly in the United States. As of August 2016, the FAA expects to see as many as 600,000 commercial drones within the next year. The word “drone” itself carries undertones most closely associated with their widespread use within the military and therefore stir certain public concern toward the technology; however, their uses have expanded far beyond military drone strikes and drones are becoming an increasingly large part of American culture. Many businesses and news organizations are beginning to integrate drones into their work while individual hobbyists across the country are taking to the sky. Understandably, both public perceptions and opinions toward drones differ depending on where, how, and by whom the drone is operated.

First, businesses are beginning to test possible uses for drones, the most common of which is delivery. Amazon’s Chief Executive Jeff Bezos reportedly announced plans to use drones to deliver packages to customers as early as 2013. As testing has continued, Bezos has commented that “the vehicle is completely autonomous. It lands by itself, and can fly more than 50 miles per hour. It has a twenty-mile range, round-trip, and can deliver packages five pounds or less.” The mere thought of drone delivery raises significant public safety concerns, such as the possibility for a drone to drop a package or crash and injure an individual. The FAA recently released new rules regulating such uses of drones, as “the new rules have almost eliminated the home delivery drone concept as made popular by Amazon.” Regardless of the legislative position, some Americans are excited about the possibility of greater convenience while other remain wary of drones delivering everything from Amazon orders to burritos and Starbucks’ beverages.

Second, drones used overseas in the name of defense and national security, especially in the war against terrorism, rally a slim majority based on a 2015 poll conducted by the Pew Research Center. The study found that 58% of U.S. adults approve of American use of drones in “conducting missile strikes from drones to target extremists in such countries as Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia.” The effectiveness of this strategy in the war against terror has been widely debated. Some argue that the drone strikes are far too inaccurate, harm innocent civilians, and add to anti-American sentiment abroad. On the other side of the debate are those who argue that drone strikes save the lives of American soldiers and are more accurate than traditional warfare. As the threat of terrorism increases public alarm, public approval for drones as a method for combatting terror threats seems to similarly increase.

When drones might be used for surveillance by police within the United States, however, many Americans take a different position. Drones raise a host of privacy concerns for the general public, as many drones are equipped with cameras or other instruments that collect data. A 2012 poll conducted by GfK Roper Public Affairs & Corporate Communications revealed a split between the 44% of respondents who support “allowing police forces inside the U.S. to use drones to assist police work” and “36% of respondents who say they ‘strongly oppose’ or ‘somewhat oppose’ police use of drones.” In light of recent protests and apprehension directed toward police practices and ethics, the mere suggestion of adding drones to police forces causes some to feel alarmed. According to Jay Stanley, a senior policy anal yst at the American Civil Liberties Union, “we know that the floodgates are about to open…Police departments will start to figure out the technology and how they can use it, and at least some of them will start to push the boundaries.” The lack of clear regulations protecting civilian privacy against possible abuses of the technology also adds to public concern.

yst at the American Civil Liberties Union, “we know that the floodgates are about to open…Police departments will start to figure out the technology and how they can use it, and at least some of them will start to push the boundaries.” The lack of clear regulations protecting civilian privacy against possible abuses of the technology also adds to public concern.

News agencies as well have begun to integrate drone technology into their work in light of recent FAA regulations that now allow limited commercial use. CNN and Sinclair Broadcast Group are on the forefront of utilizing drones in news reporting. Sinclair Broadcast Group hopes to have “80 trained and certified UAS pilots working in 40 markets by the end of 2017, and already has launched UAS teams for newsgathering in Washington, DC; Baltimore, MD; Greenbay, WI; Columbus, OH; Little Rock, AR; and Tulsa, OK.” Drones offer news organizations a cheaper, easier way to gather video and images of events and allow them access to areas that would otherwise be difficult to access. FAA rules that took effect on Aug. 29, 2016, “come with a number of operational limitations on UAS operation. However, if a party can demonstrate the ability to operate safely while deviating from a specific limitation, the FAA may grant a waiver of one or more of the specific limitations found in its rules.” Within the context of newsgathering, regulations must balance freedom of speech protected by the Constitution as well as protect citizens’ privacy and safety.

Perhaps one of the greatest public concerns toward drones is toward individual hobbyists. Currently, the same regulations do not apply to hobbyist drone pilots that apply to law enforcement, businesses, or news organizations, yet hobbyists also have the capacity to gather images, video, and other data. The U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Telecommunications Information Administration (NTIA) has released a list of voluntary best practices for drone pilots that attempt to protect privacy in private areas, such as avoiding flying over private property and avoid keeping images and videos for as little time as possible. Here as well, the lack of clear regulations has caused significant public concern toward drones. Currently, “anyone can walk into a Fry’s Electronics or Samy’s Camera store and buy a quadcopter with a camera for less than $100 and have it zipping through the sky in minutes. No instruction, no registration and no requirement to know the rules governing airspace. And, often, no clear understanding of the havoc one plastic toy can cause.”

Distinct sides seem to have emerged surrounding the issues of drones and privacy: those who focus primarily on the myriad of possibilities and benefits drones can yield, ranging from safer and more thorough search and rescue efforts to brilliant photography, and those who are instead concerned with the various ways in which drones might be used to invade or violate another’s privacy, such as hovering above a backyard. Currently, public opinion toward drones within the United States focuses on privacy and safety concerns, regardless of whether the drone is used by law enforcement, news organizations, business, or hobbyists. As a result, local governments have responded with laws mostly responding to these concerns in the absence of federal regulations. According to a recent survey by the U.S. Postal Service, “75 percent of Americans say drone delivery service will be offered in the next five years” and Americans are growing used to the fact of drones in the skies; however, concerns still exist, as “only 32 percent of Americans think that the drone delivery will be safe” and “some 37 percent think it would not be safe.” Despite the fact that recent tests of delivery drones have proven successful, the concern is nevertheless present and the majority at present seems to lean more cautiously toward drones. Regardless, it is clear, from their increasing range of uses to debates regarding how best to enact regulations, that drones will only take a larger role within American society in the coming years.

Politics & Law

Corey Schulz, Stuart Motta, Connor Jensen, and Ben Anderson

Though drone rules and regulations passed by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) are plentiful, drone laws in the State of Utah are sparse. As things currently stand, the FAA (under the Executive Branch of the US government) and the State of Utah can both enact rules to limit drone use. This section will focus on drone laws passed by the State of Utah.

Statewide Laws

There are two predominant pieces of legislation passed by the Utah State Legislature that apply to Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) technology within the state’s legal jurisdiction. The first of those bills is SB0167, “Regulation of Drones,” from Utah’s 2014 congressional General Session. SB0167 has been in effect since April 1st, 2014. The most noteworthy thing in this piece of legislation is that it enacts the “Government Use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Act”, which is the bill’s main focus. That specific act prohibits a law enforcement agency from obtaining data through an unmanned aerial vehicle unless the data was obtained either in accordance with a warrant or with judicially recognized exceptions to warrant requirements (Utah Code § 63G-18-103(1)(a-b)). The bill also establishes requirements for the retention and use of data collected by a UAV and instantiates reporting requirements for a law enforcement agency that operates UAVs (Utah Code § 63G-18-103(3)).

SB0167 limits what Utah’s law enforcement agencies can do with drones. They have to stay within the bounds of the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution when it comes to data collection and illegal search and seizure via UAV technology. In a minor but still significant role, the bill also defines terms to be used in Utah’s court system. Terms such as “law enforcement agency,” “nongovernment actor,” “Unmanned Aerial Vehicle,” among others now have legal definitions within the state of Utah for future pieces of legislation and court proceedings (Utah Code § 63G-18-102). This bill constitutes the entirety of Utah Code Title 63G, Chapter 18, Sections 101-105.

SB0167 limits what Utah’s law enforcement agencies can do with drones. They have to stay within the bounds of the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution when it comes to data collection and illegal search and seizure via UAV technology. In a minor but still significant role, the bill also defines terms to be used in Utah’s court system. Terms such as “law enforcement agency,” “nongovernment actor,” “Unmanned Aerial Vehicle,” among others now have legal definitions within the state of Utah for future pieces of legislation and court proceedings (Utah Code § 63G-18-102). This bill constitutes the entirety of Utah Code Title 63G, Chapter 18, Sections 101-105.

The second main piece of legislation that affects UAV technology within the State of Utah’s jurisdiction is HB3003, “Unmanned Aircraft Amendments,” from Utah’s 2016 congressional Third Special Session. HB3003 has been in effect since July 17th, 2016. The bill alters the penalties relating to operating UAV technology near/inside of certain wildfire areas. Within Utah it is now a class A misdemeanor to operate UAVs in a way that prevents aircraft meant for wildfire control from taking flight or otherwise performing their duties (Utah Code § 65A-3-2.5(3)). The bill also authorizes a judge to make the defendant of the crime pay restitution. The most controversial portion of the bill, however, is that the legislation allows for the neutralization of unmanned aircraft in certain circumstances. The chief law enforcement officer of a jurisdiction or the incident commander of the wildfire area has the power to order the UAV shot out of the sky or otherwise neutralized if that UAV is in violation of the policies discussed earlier (Utah Code § 65A-3-2.5(6)). This bill constitutes the entirety of Utah Code Title 65A, Chapter 3, Section 2.5.

In a nutshell, the two pieces of legislation, HB3003 & SB0167, are what define the drone landscape in the State of Utah. SB0167 restricts governmental use of drones and HB3003 restricts personal use of drones when they oppose wildfire fighting initiatives. Both Utah’s own drone laws and the FAA’s drone rules apply within Utah’s jurisdiction.

Drone Laws in Parks and Local Areas

While there are explicitly defined laws regarding the use of drones in the state of Utah (published under Utah Code), there are many more restrictions that municipalities and similar entities have enacted. While the legality of these laws could likely be successfully challenged in a court of law, common courtesy dictates that they are minded. Examples can be seen in everyday instances- stadiums, public and state parks, and various townships. While the use of UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) in national parks has been expressly forbidden by the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration), there is no mention of state parks, for obvious reasons. Dead Horse Point state park has banned the operations of drones between the months of March and October, in an attempt to protect people’s privacy and enjoyment of the park. Antelope Island state park outright bans the use of drones, for unstated reasons (likely of a similar ilk to Dead Horse Point), with exemptions for special use. Antelope Island’s special-exemption-only-flight isn’t inherently bad, especially considering it serves both as a recreation area and a wildlife preserve. While the determined individual could likely fight such a law with varying degrees of success, time and money expenditures would render a victory bittersweet. The bad publicity inevitably following such a case would only worsen the relations between the general public and drone enthusiasts.

In addition to the variety of laws/policies passed by state park administrators are those enacted by public parks and recreation areas. Sugarhouse park in Salt Lake City currently prohibits the use of drones on park premises saying, simply, “no powered aircraft.” Falcon Park actively supports the use of models to an extent, provided they are flown within the FAA guidelines. There is no central resource for finding these laws, but landowners make very clear when they do not want drones flown within their proximity. Posted signs and public notices, especially around holidays (notably the 4th of July), make these intentions clear, even if the solution is only temporary. Landowners do have the right to prevent the takeoff and landing of aircraft on their property, but common courtesy should prevail regardless.

Drones’ utility in regards to filming action sports has also spurred decisions on behalf of Utah ski resorts. Currently, there are no ski areas that allow unrestricted use of drones. The divide between restrictions and complete bans are an even split for the remaining resorts. Those that restrict flight to special waivers are as follows:

- Brian Head

- Eagle Point

- Nordic Valley

- Powder Mountain

- Snowbasin

- Snowbird

- Sundance

Those who ban UAV use outright are:

- Alta Ski Area

- Beaver Mountain

- Brighton

- Cherry Peak

- Deer Valley

- Park City

- Solitude

Crashes while skiing and boarding are a messy business, and the aforementioned constraints are presumably not malicious in intent. The intent of drone control should be public safety, with a lesser consideration to comfort. Drone enthusiasts might disagree with this sentiment, but flight restriction over ski resorts during season are justified.

Drone control is not going away, that can be said with great confidence. But the voice of the people can help tell us why it may have become law. On a KSL article regarding drones and privacy concerns, Chad M. has the highest rated comment with, “Regardless if they are a drone or a r/ plane, they are going to make good target practice”. Though this cannot be interpreted as the opinion of everyone in Utah, it does go to show there are people that think in this manner. Unfortunately for these people, the government has classified such an act as a felony, punishable by up to twenty years in a federal prison. As a result, the legal status of shooting down aircraft is unlikely to change, regardless of the opinions of Utah residents. On the contrary, a poll from the same article states that 54% of responses say that drones are a good hobby, introducing the more nuanced views of citizens. Another article, detailing potential ways drones could be of use in everyday life has also garnered criticisms. DIndedpendent claims that, “George Orwell must be spinning in his grave. By the time everybody objects to having electronic trackers placed under our skin for our own convenience it will be too late to demand privacy.”. A tentative conclusion can be drawn from these and other opinions found on Utah’s news websites. That is, drones and their operations are not evil or bad in normal operation, but they instantly become the devil incarnate when they encroach upon the privacy rights of others. Drones interfering with wildfire-fighting efforts has also been a source of negative press. A large number of people don’t seem to realize that this is already illegal under the FAA’s section 336, stating that drones must yield right of way to manned aircraft. Bloodlust for the offending drones has even pushed Utah to pass laws adding to the FAA’s interpretation.

Federal, State and Local Laws Compared

Utah as a state accepts  all of the FAA’s regulations as their own. However Utah adds some of their own laws. Many of which are similar with what the the FAA says. There are 5 national parks in Utah, all of which have banned drones. This is consistent across the country, all national parks have opted to ban drones. The addition of the wildfire law that states you cannot fly a drone within a specified distance of a wildfire, this also differs from federal law (NCSL). This is important for Utah and the drier western states, due to how common wildfires are the air traffic in these areas drones could be considered a danger for other aircraft coming to the area. The state considers this a serious issue due to the harshness of the punishment. If a drone flying near a fire stops an aircraft from flying or dropping a water retardant, the operator could face fines of up to $2,500 and jail time. If a drone collides with an aircraft or causes it to crash, the maximum punishment includes 15 years of jail time and a $15,000 fine. However, the FAA’s penalty for not registering a drone includes civil penalties up to $27,500. Whereas the Criminal penalties include fines of up to $250,000 and/or imprisonment for up to three years (FAA). The Federal punishment is much more severe for not following the rules and regulations the FAA set up. Utah has allowed the police and firefighters responding to wildfires to disable drones that interfere with the wildfires, this can only be ordered by an officer (Dronelife). However, the FAA has said shooting drones down is a federal crime. But, drones cannot be obtrusive or invading one’s privacy. This is mainly for drones being flown by someone’s property. Utah’s law also prohibits the use of data collected by drones without a warrant. Most states have similar rules stating you must first acquire a warrant before using information collected from drones as official evidence (Brookings). Property rights must also be taken into consideration in both cases.

all of the FAA’s regulations as their own. However Utah adds some of their own laws. Many of which are similar with what the the FAA says. There are 5 national parks in Utah, all of which have banned drones. This is consistent across the country, all national parks have opted to ban drones. The addition of the wildfire law that states you cannot fly a drone within a specified distance of a wildfire, this also differs from federal law (NCSL). This is important for Utah and the drier western states, due to how common wildfires are the air traffic in these areas drones could be considered a danger for other aircraft coming to the area. The state considers this a serious issue due to the harshness of the punishment. If a drone flying near a fire stops an aircraft from flying or dropping a water retardant, the operator could face fines of up to $2,500 and jail time. If a drone collides with an aircraft or causes it to crash, the maximum punishment includes 15 years of jail time and a $15,000 fine. However, the FAA’s penalty for not registering a drone includes civil penalties up to $27,500. Whereas the Criminal penalties include fines of up to $250,000 and/or imprisonment for up to three years (FAA). The Federal punishment is much more severe for not following the rules and regulations the FAA set up. Utah has allowed the police and firefighters responding to wildfires to disable drones that interfere with the wildfires, this can only be ordered by an officer (Dronelife). However, the FAA has said shooting drones down is a federal crime. But, drones cannot be obtrusive or invading one’s privacy. This is mainly for drones being flown by someone’s property. Utah’s law also prohibits the use of data collected by drones without a warrant. Most states have similar rules stating you must first acquire a warrant before using information collected from drones as official evidence (Brookings). Property rights must also be taken into consideration in both cases.

The Future of Drone Laws

Since we have now covered what the current drone laws are, we can now look at how drones laws may change and evolve in the future. One of the more restrictive aspects of the current FAA restrictions is the need for pilots to keep line of sight with the drone. This puts a fairly large obstacle in the way of companies like Amazon who are looking for drone technology to be used as a means of delivery. The need for line of sight on drones means that any automated operations are not currently possible. Regulations like this will need to either be removed or modified so that only those who prove themselves capable (through licenses or other means) may have the freedom to fly drones with less restrictions.

Another regulation that may need to be created in the future is one regarding airspace. Public airspace is currently anything over 400 ft. and drones are allowed to fly below that. But, if U.S. aviation officials are correct, there could be as many as 7 million drones attempting to share a small airspace by the year 2020. This sheer volume of drones may require its own designated airspace, especially if a large portion of these are commercial drones being flown autonomously. Just as aircraft need traffic controllers, drones may need their own. NASA is working with Google and Amazon to try to come up with a solution. One of these is NASA’s UAS Traffic Management System which would track drones and send alerts to operators about numerous important hazards such as weather and restricted airspaces.

This 400 ft. maximum also limits companies who wish to do maintenance checks on larger structures such as skyscrapers and nuclear power plants. More isolated businesses such as power plants, that tend to have a safe distance from crowds of people may not have trouble securing exemptions from this rule, buildings in cities that wish to do similar things may need more innovation in drone safety to ensure these drones won’t fall from the sky and injure pedestrians.

Drone law is most likely going to need to change quickly and often, just as drones are at the moment. If the FAA stays on top of how drones are being used and how they might be used in the future, drone laws might not be as much of a hassle as they were when drones first came to the mainstream.

Economics & Industry

Olivia Juarez, Cole Perschon, Alexander Reifsnyder, and Keegan Vanleeuwen

Over the past several years, Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), otherwise known as drones, have integrated into the Utah economy. The Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) predicted an economic impact in Utah of $859 million in the next 10 years (2015-2025) which would lead to over $7.26 million in state tax revenue and over new 1,085 jobs. In 2016, the economic impact of drones in Utah is expected to be as much as $47 million dollars which is a 101% increase from 2015. Marshall Wright, the Director of Business Development concerning Aerospace and Defense at the Utah Governor’s Office of Economic Development states, “The future of drones is very bright. It is one of the most innovative areas of Aerospace. Technology from the use and applications of ‘commercial drones’ will impact all aspects of aviation. It will affect how air traffic management will be accomplished in the future. Much of the control technology for safe operation of drones will find its way into general aviation and will make it safer as well. This is a very exciting time for aerospace in Utah.” UAS technology has sparked profitable new and creative industries within the Utah economy. These industries include aerial photography, agriculture, videography, and drone production.

Aerial Photography

One of the most valuable commercial drone industries in Utah is in aerial photography. Typical aerial photography products in Utah include real estate, construction, inspections, engineering projects, and weddings/events. In the past few years, countless large and small drone photography companies have popped up in Utah; companies such as SilverHawk Aerial Imaging, Quad Capture, and Wasatch Aerial Photography. Large aerial photography companies typically commercialized business to business rather than business to consumer like SilverHawk Aerial imaging, who focus their photography toward government agencies, infrastructure inspections, engineering projects, 3D modeling, and much more. Small aerial photography companies and individual drone pilots typically market to consumers or small businesses, and many make their debut through the droners.io forum. Established 18 months ago by entrepreneur and drone enthusiast, Dave Brown, droners.io is a marketplace for individual drone pilots and drone companies. For just a 10% profit cut, over 2,000 individual pilots market their services through this website. In Utah, droners.io has helped kick start and market over 60 local drone photography businesses. Local aerial photography company, QuadCapture started using droners.io in May. QuadCapture was founded in March of 2016 by Caleb White, and focuses their photography toward television marketing, real estate, weddings, and tower inspections. In the future, many Utah aerial photography companies would like to see commercial drone manufactures produce a product specifically for commercial drone pilots.

While the new FAA commercial drone law (revised Part 107) makes becoming a commercial pilot easier, both SilverHawk and QuadCapture agree that the quality of the drone photography industry has decreased with the sudden increase in drone pilots. The FAA Part 107 regulation is a set of ground rules for commercial pilots whose drones are under 55 pounds. Regulations include: no flying above 400 feet, visual line of sight, no night flying, speeds under 100 mph, airspace restrictions, and a passage of the remote pilot airman certificate with a small UAS rating. After the regulation passed, the aerial photography industry was flooded with inexperienced hobbyist pilots who wanted to turn their skills into profits. “Smart companies stick with older and more experienced pilots rather than being price driven,” says Dave Terry, the CEO of SilverHawk Aerial imaging. Before FAA Part 107 revision, commercial drone pilots were required a FAA certified pilot’s license, which gave aerial photography companies a higher value. Caleb White, the founder of QuadCapture, says before the new FAA Part 107 regulation he had an advantage in the market due to being an experienced airline pilot, but now since becoming a FAA certified airline pilot is no longer a requirement, it seems like anyone with a drone can start a aerial photography company. Currently, however, the FAA has a small but active program creating Certificates of Authorization which allow commercial pilots to venture outside of its regime. The FAA Part 107 is the first of many regulations that are coming in the near future for commercial UAS.

While there are new emerging markets for aerial photography like radio and cell tower inspections, real estate photography still remains one of the largest in Utah. By 2020, the FAA estimates the real estate industry will hold 22% of the drone market nationwide. For most aerial photography companies in Utah, the real estate industry is their most frequent client. Ravath Pok, principle broker of Signature Group Real Estate says he first started using drone photography five years ago when prices were four times than what they are today. Very few drone photography companies existed five years ago, and real estate firms like Signature Group hired from individual pilots that they were referred to. For local real estate companies like Signature Group, the creativity of the pilots and the unique perspectives of the shot are much more important than the price. With the advancement of drone photography, Signature Group is able to give unique virtual tours of their homes which drives up the value for their customers.

Agriculture and Inspection

There are many niche industries that contribute to the drone industry in Utah. Drones have the ability to be implemented in a variety of dangerous or difficult for humans. One such industry is agriculture. Many agricultural applications like crop-dusting and plant health monitoring traditionally require expensive aerial platforms like helicopters and airplanes along with human pilots that have to put their lives on the line to help deliver vital crops to our tables. Drones can alleviate some of the danger of these essential tasks. One Utah company: Aggie Air, has taken the charge to bring agricultural drones to Utah. Aggie Air’s drones are fixed wing designs, not the traditional “quadcopter” style UAVs that many people now think of upon hearing the word drone. The drones that Aggie Air makes are nowhere near capable of replacing all manned tasks, but they are an important stepping stone.

Drones also serve an important function as remote inspection vehicles. According to Droners.io, a Utah born company, inspections for roofs is the 3rd largest user of their drone services. Roof inspections are required for many things, one of which is insurance claims. In order to validate that an insurance claim is valid the roof must be inspected. Inspections are normally carried out by hand and can take a long time, be expansive, and dangerous to the operator. Using drones to inspect roofs could help to solve these problems.

Roofs are not the only thing that need to be inspected. Nuclear fuel ponds also need to be checked for integrity every now and then. The TRIGA research reactor on campus is one such piece of equipment that needs inspection for soundness. Though the reactor team declined to comment, typical nuclear reactors are inspected every 18 months as they are being refueled. The time interval for the TRIGA reactor is likely slightly less frequent, but almost certainly at least once every two years. Using a drone to do this could save cost and time, not to mention improve safety. An autonomous or remotely piloted vehicle could get much closer to some parts of the reactor that a human can’t. Even things that were safe when they when into the reactor can be made dangerous by the intense radioactive energy of the core. Drones can help people from having unexpected dangerous interactions like this one, told by Randall Munroe.

Videography

Utah is a special place for cinematography due to the unique and beautiful natural environment sought out by artists and the outdoor recreation industry alike. According to Ricardo Flores, Marketing & Creative Executive at the Utah Film Commission, “The Utah Film Commission is a state agency that markets the entire state for production filming. That includes (not limited to) features, series, commercials and photo shoots. We market the state by promoting the use of Utah locations, local professionals and vendors.” As part of marking the state of Utah as a place to film, the Commission also must facilitate emerging film technology, specifically unmanned aerial systems (UAS), into safe and legal use for videography in Utah. Flores states that in the film industry the term “drone” is more popularly used although UAS would be more correct.

“Drone operators” are persons who fly and film with UAS at the same time, now with the need of an FAA UAS operator license to put their talent to legal use. Flores argues that this stipulation is a minor holdback since the FAA requires an additional certificate of authorization (COA) for a specific type of flight such as closed set filming. In other words, FAA-licensed UAS pilots must still obtain an extra document permitting the pilots to fly in regular filming environments, which the FAA deems as special settings. Flores states that the FAA is not clear on this COA stipulation, and that the misconception probably means that some operators “are not “legal” to fly commercially.” Here, we can see that Utah’s industry-specific organization can offer the FAA a new perspective on how to best communicate to drone operators to improve safety communications.

The Utah Film Commission also maintains a directory where anybody in the filmmaking industry can search for UAS services such as camera operators, pilots, equipment rental, and production companies. Their directory includes six different entities who specialize in a combination of the services listed. In addition to these entities exists three Utah production companies who have fully integrated drones into their overall production criteria, and five major pilots and companies who have been filming with drones in Utah the longest.

The Utah based production companies, Avalanche Studios, Cosmic Pictures, and Lone Peak Productions have integrated drones into their overall production criteria. Their expertise in UAS operation may be not as specialized as one might find in a production specific company since many of these businesses have focus on post-production services. To meet the demand Utah is home to more than six companies and individuals with expertise in UAS cinematography.

- Camp4 Collective is another Utah based company who could not be reached for contact. Their clientele includes The North Face, AMTrak, Apple, BF Goodrich tires, and more.

- The downtown Salt Lake City based company, SuperTopSecret Studios (STS), has been using drones for production since 2012. Dave Trevino, Director of Photography at STS, states that STS serves action sports clients like Goal Zero, Red Bull, Skullcandy and Cotopaxi. Other prominent clients served with drone operation include Nike, Oakley, Ski Utah, and Powder Mountain. About 60% of STS’ client work is filmed in Utah. On the FAA’s new commercial rule permitting commercial use, Trevino believes that it will make airspace safer. However, he states “the restriction on flying at night is restrictive.” After all, which of the most popular programs do not take place at night at some point?

Most notably, Trevino highlighted the importance of STS being able to use drones in their company. “We use drones on almost every shoot – even if we are only up in the air for 2 minutes to get an establishing location shot. Clients are very happy when they hear they can keep all of production with one company. Our annual revenue is anywhere between $400,000 – $750,000 per year.” A significant portion of that revenue is secured by the fact that clients can streamline business within one company instead of needing to contract auxiliary drone operators. Trevino ends by stating that drones are much better built and priced now than they were just four years ago, “we [at STS] are really tied to their developing technology at all.”

- Override Films is another South Salt Lake City, Utah based business which boasts having 213 customers, 2280 logged flights on projects, 10 years in aerial productions, and 22 years in production overall. Some of their clients include Oakley, Snowbird Resort, Crescent Dunes Solar Farm, Samsung’s Olympics Aerials, all of whom have done business with Override for their expertise in the realm of aerial cinematography.

- Finally, Utah is home to two prominent YouTubers, Devin Grahm and Scott Winn. Filming since 2010 and 2006 respectively, these videographers have made popular videos in recognizable Utah landscapes such as Ogden suburbs and the University of Utah campus.

Utah is a booming place for the film industry, and home to a number of talented aerial videographers. The prolific recreation economy in Utah attracts major sporting enterprises, compounding the value of Utah as a place to both recreate and film the state’s unique amenities.

Drone Production

Since you have now heard about many of the different industries in Utah utilizing drone technology, we’ll shift to the production of drones in Utah. Teal, the only drone design, production, and manufacturing company in the United States, is located right here in Salt Lake City. A sit down interview with the company’s President and Chief Executive Officer George Matus, produced much insight on what it is like pioneering drone technology here in Utah. Teal, “the world’s fastest production drone”, has been an idea and a work in progress of George’s since he was 16. The company had its humble beginnings, born in Matus’s basement while he was still in high school, his technology was coming along slowly but surely. The major turning point for Matus happened just after a proof-of-concept presentation Matus did at Stanford, when he met billionaire Peter Thiel. He later won serious funding and a fellowship from Thiel in mid 2015, where Matus was once more enlivened and inspired to chase his dreams and pursue the path of starting his drone company.

Teal, launched in Q2 2016, is now nearly a month away from shipping its first round of production drones to consumers, but has had to overcome many hurdles along the way. iDrone, as the project was originally called, an easy naming choice for an “Apple super-fan” such as Matus, was born from a wishlist Matus had created throughout his adolescent years flying many different UASs. He outlined everything he wanted from a drone, the only logical next step for a 16 year old was to start his own company. One of the drone’s central features, and something that really sets Teal apart from the competition, was the incorporation of an onboard microprocessor, the Nvidia TX1. A small integrated computer that outperforms, by leaps and bounds, all other similar incorporated systems on competing drones. The TX1 allows Teal to handle “machine learning, autonomous flight, image recognition, and much more with ease, onboard the drone itself.. You can even plug Teal into a monitor, use it like a normal computer, play games on it, and go fly when you want!” Teal truly is an amazing product and it comes in at an unbeatable price, how has Utah shaped its development?

Building a drone startup from the ground up, here in Utah, offered some unique challenges and opportunities for Teal. According to Matus, Utah is a great place for a drone startup company. “There’s a growing startup culture here, a great talent pool, and benefits of lower burn rate and overhead costs.” (Matus) Albeit Utah does have a smaller startup culture compared to elsewhere, so “it’s a little more difficult finding a lot of talent to join at an early stage.” (Matus) However, he believes that Teal has an excellent team now. Matus also stated that Utah has presented Teal with different applications for the product that may not be found elsewhere. The mountains, for instance, have provided specific opportunities for commercial endeavors, such as Search and Rescue. Getting the TX1’s toes wet into the development of commercial drone software. “From gaming and augmented reality, security and inspections, e-commerce and agriculture, to purely simplifying and automating drone flight, the opportunities are truly endless. Teal is the only drone designed to be a platform for all of these multiple uses.” (Matus)

Another UAS manufacturer located here in Utah, Rocky Mountain Unmanned Systems (RMUS), serves a different flavor of drone. A spin off from a local hobby store, starting in 2013, RMUS was born from HRP Distributing. Now, RMUS currently operates from its’ headquarters down in Orem, however, is known internationally as a major exporter of customized variants of popular commercial drones like the DJI Inspire 1. The appeal to RMUS’s products is that they are designed specifically for various commercial applications ranging from Search and Rescue to Agriculture, with everything in between. For example they have a model of the DJI Inspire 1 intended for Law Enforcement that features a FLIR camera, lighting system, transponder system, and more. They are at the forefront in Utah for commercial drone development and have a large variety of models and technologies being utilized on their drones worldwide, all used for many different commercial applications.

Along with the growth of industry, the implementation of drones in the Utah economy has also sparked alliances for further education and development of commercial drones. Utah’s own Mountain West Unmanned System Alliance (MWUSA) exists to “make the State of Utah the example of responsible commercial use of unmanned aerial systems” according to Ryan Wood in a Utah Governor’s Office of Economic Development (GOED) statement. This is specifically beneficial for entrepreneurs and small business owners supported by MWUSA Membership. Members include the GOED, the Utah Film Commission, Rocky Mountain Unmanned Systems, Utah Valley University and several local film and video production companies to establish Utah as a viable hub for UAS industries and economic development. The alliance is encouraging additional membership from private and public institutions, enhanced research opportunities, and supporting a sustained economic impact in the Utah economy.

Overall, the local combination of private companies, public safety applications, and organizational alliances indicates that the State of Utah is establishing itself as the number one place for UAS integration into the local and national economy. Utah is a national hub for UAS innovation and implementation in commercial enterprise and will likely lead the nation in development of this rapidly growing economic sector.

Science & Technology

Erik Mollinet, George Eltzroth, Nicolo Young, and Vincent Young

Drones are a unique tool for research that have been developed over the last several years. Drones, or Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV’s) are small flying robots, usually with four, six or eight propeller blades. They can be fitted with small cameras and other sensors, which allow a unique perspective on the world for film, news reporting, and hobbyists. Drones are also very useful as a research tool for scientists, as they allow data collection in areas that are normally beyond the reach of a standard grad student or researcher. They allow one to get a bird’s-eye view of the world, and collect data for research from several hundred feet above the ground. Scientists have used them to map untamed wilderness, take air samples, and much more. Other scientists and engineers develop new technologies for drones, making them lighter, cheaper, and more effective. In this section, we are going to profile just some of the people who have been using drones in their research, or researching technologies for drones, both at the University of Utah, as well as at other universities in the state of Utah.

University of Utah

Alex Koch – Researcher

- Department: Geology

- What they do: Alex uses drones for mapping terrain features in various locations in southern Utah. Primarily he studies ancient riverbed canyons, which have exposed cliffs with many layers of rocks. He collects data using a DJI drone, then uses a photogrammetry program to stitch the images together into a three-dimensional image of a site. By doing this, he and his department are able to identify and locate porous rocks that could contain oil.

- Why use drones?: Alex says he uses drones because they are much cheaper than other alternatives for gathering data for this type of research. Previously, his department has needed to use a helicopter, which is much more expensive. By using a drone, they can collect data much more cheaply, and thus collect more data.

- Problems with drones: The main problem they run into in their research is regulatory. In particular, it can be difficult to obtain permission to fly in certain areas, like national or state parks. FAA regulations also cause problems, but have improved recently.

- Technology: The drone they use is a DJI with a high-quality camera and a GPS unit onboard. The drone takes pictures every several seconds, recording its orientation and position. This lets the photogrammetry software combine hundreds of images into a single virtual space by matching up similar features in the pictures. Alex says that in the future, a LIDAR system, which uses lasers to find precise distances, could be mounted on their drone to gather more precise data.

John Horel – Professor

- Department: Atmospheric Sciences

- What they do: John uses a drone to map atmospheric conditions in a column of air in the Salt Lake Valley. They use a variety of sensors to measure air quality, humidity, pressure and more.

- Why use drones?: Drones offer several advantages over normal methods of collecting data in this field, such as weather balloons or helicopters. For one, drones don’t use helium like a weather balloon would, thus conserving non-renewable resources. However, they can use the same cheap, simple sensors that a balloon would, rather than needing modified sensors for a helicopter or other method of data collection. In addition, it is significantly easier to recover the sensor payload from a drone, because it is pilotable. This reduces environmental impact from lost balloons and allows more data to be collected. Finally, a drone can hover, collecting data for a specific altitude over a period of time, rather than constantly ascending like a balloon.

- Problems with drones: While drones are very useful for this kind of research, they do have drawbacks. For instance, they can only fly below 400 feet as per FAA regulations right now, and have short battery life. It can also be difficult to measure wind speed and direction, because the drone is not expected to move laterally with the wind while collecting data, unlike a balloon. Drones are also limited to relatively good weather, while balloons can be released any time.

- Technology: John uses a large quadcopter, built and modified for collecting atmospheric data. He added lightweight atmospheric sensors to a stock body, as well as a pivoting arm with a goPro camera. All the equipment used is fairly standard, but the combination of sensors used, mounted in a styrofoam coffee cup body for easy retrieval, is fairly unique.

Casey J. Duncan – Ph.D. Student

- Department: Geology and Geophysics

- What they do: Casey’s research includes developing low-cost alternatives to autonomous mapping planes and multispectral camera technology by using low-cost construction materials and readily available components. There is a definite need for further development of low-cost technologies in this area. As Casey describes, “Commercial autonomous mapping planes are outside the price range of many undergraduate to graduate researchers, non-profit organizations, community organizations, and STEM educators with the cheapest systems starting at ~$3000, often exceeding $5000, and multispectral cameras tacking on an additional ~$3500 at least.” Utilizing low-cost construction materials such as foam board and hot glue in the development of the aircraft as well as readily available components such as Raspberry Pi computers and camera modules in developing the multispectral camera, Casey is able to “build a fully autonomous mapping plane and multispectral camera for ~1/10 the cost.” That’s ~$500-$850. Casey also uses UAVs, both quadcopters and fixed wing aircraft, for research at a field site in Nevada. Here the UAVs are used to produce maps and 3D surface models of rock outcrops. As Casey states, “With the incorporation of multispectral imagery, I will also be able to map out the distribution of minerals within my field area. Getting such high resolution imagery is key for fully understanding how the rocks in my field area formed.”

- Why use drones?: Both mapping and creating 3D surface models would have required full-size aircraft or satellite imagery if drones were not used. Drones act as a low cost platform for the multispectral cameras. Drones also have benefits over traditional research methods. Imaging large areas and rock formations traditionally required a lot of hiking, drones can quickly image large areas and produce actionable data allowing for “understanding of broad patterns presented within rock formations much faster and more accurately than traditional methods.”

- Problems with drones: The single biggest problem related to drones that Casey has found during research is navigating FAA regulations. Although a Section 333 exemption and a COA are no longer required, the FAA does require Casey to comply with Part 107, which allows for research/commercial use of UAVs.

Kam Leang- Professor

- New technologies being researched/developed: Professor Leang is working to develop a new drone platform which will be used in his future research. He is working to get the new platform to hit target specifications for weight, collision avoidance, and autonomous flight. The technologies which are being developed and employed on the new drone platform include motion planning and collision avoidance algorithms to improve the drone’s autonomy and decision making. The goal is to have the drone ready to perform its intended functions, including chemical detection and localization, starting next year. Existing technologies which are being employed on the new research platform include chemical sensors, as well as single board computers.

- Challenges: The biggest challenges faced in this research center around the autonomous flight capability of the drone platform. This includes developing and improving algorithms for collision avoidance, decision making, and motion planning. Additional challenges are those faced by all drones, such as limited flight time.

- Drones in the Future: In the near future, drones will likely play a larger role for public safety, including emergency response services and search and rescue. With the increasingly economical possibility of autonomous flight, insurance companies may also find drones more useful for applications such as surveying roof damage after a storm. When asked about drone package delivery and other suggested applications for drones in the near future, Professor Leang said he’s skeptical. Drone package delivery is a neat idea but it would be tough to implement. The role of consumer UAVs will likely not change significantly in the near future as hobbyists will continue to use their drones for aerial photography and similar applications.

- Drones in Research: Professor Leang plans on using drones for sensing and detection of chemicals in the air as well as localization of the source of such chemicals. As compared to other research tools, drones provide a greater degree of motion and versatility. Drones are also comparatively cheap and they save time in the field, which translates into additional economical benefits.

- Concerns About Using Drones: Professor Leang’s primary concerns about drones are related safety and privacy.

- Drones in Future Research: Professor Leang plans to continue using drones for chemical detection and localization, and would also like to use them for more environmental monitoring and agricultural applications.

Utah State University

In 2008, researchers at Utah State University launched AggieAir, an autonomous flight control system for monitoring bodies of water and agricultural land. The system consists of three key components: the drone, a sensor package, and a ground station. The drone navigates using a flight path that is programmed ahead of time, and can carry a wide array of sensors including visual light, near-infrared, and thermal infrared cameras, as well as air quality and biotelemetry sensors. The ground station consists of a laptop computer and a wireless telemetry link, and is constantly exchanging data with the aircraft. Also included is a Safety Pilot, which can be used to manually control the aircraft if needed. The AggieAir fleet currently consists of five different aircraft with wingspans ranging from 4 to 10 feet. The system can be used to monitor vegetation health and ecological integrity, and has been used by organizations such as The Nature Conservancy to monitor rivers and other ecological systems.

The Computer Science Department at USU is modeling human workload in unmanned aerial systems. This research is entirely simulation based, modeling the human operators of a UAS as finite state machines with simple external memory. The simulation is meant to generate workload profiles that mimic the amount of work that must be done by humans in each scenario. By comparing the data from simulated wilderness search and rescue scenarios with known data about the actual workloads involved in such systems, the researchers have determined their models to be consistent with reality. The purpose of this research and the resulting simulation is to determine the number of human operators a given UAS will require to be effective. However, in order for the data to be meaningful the researchers say they will need to conduct experiments with real human operators, and more carefully survey existing data.

Brigham Young University

A group of students at Brigham Young University is using UAVs to monitor infrastructure. Specifically, they are looking into using drones to improve the long term sustainability of flood protection structures like levees and embankment dams. At the current stage they have not yet implemented autonomous flight, but the goal of the project is to eventually use autonomous aerial and ground robots to collect images of crucial infrastructure. The collected images are used to automatically construct 3-dimensional models of the structures and identify any potential anomalies and faults.

Another group at BYU is working on “Multiple Agent Control,” which is when multiple agents, in this case drones, are all controlled in part by an overarching system. According to the researchers, splitting up control across multiple agents “improves the ability to explain controller action, reduces development costs, and allows sub-sets to be revamped without changing the other agents.” Their tests consist of three components, each with its own autopilot functions. A large drone called the mothership flies in a circle and tows a drogue on a cable. The drogue has an autopilot component and some ability to move itself, which it uses to maintain a smaller circle below the mothership. It also carries a homing beacon, which the third agent, a Miniature Aerial Vehicle (MAV), flies towards and attaches to. The purpose of this system would ultimately be to recover MAVs once their task has been completed without the need for a landing pad, runway, or parachute.

Society & Culture

Peter Davidson, Donovan Wixom, Scott Foden, Cameron Shonnard, and Ian VanLeeuwen

Peter Davidson, Donovan Wixom, Scott Foden, Cameron Shonnard, and Ian VanLeeuwen

What do people in Utah think about drones? What do people use drones for? Does anyone ever think about the impact of drones? These are some of the questions we wanted to answer. We wanted to find out if people – primarily students – had real and valuable opinions about drones.

This section of the report began with interviews outside the Marriott Library on the University of Utah campus. Each interview was recorded by Scott, Peter, and Cameron using two high-definition cameras and a handheld recorder for high-quality, professional video and sound. Scott, on the spot, interviewed twelve students ready to give their opinions about drones. At the same time, Donovan and Ian used their smartphones to administer web surveys to the outskirts of campus, polling unsuspecting students at random with a variety of drone-related questions.

Polling

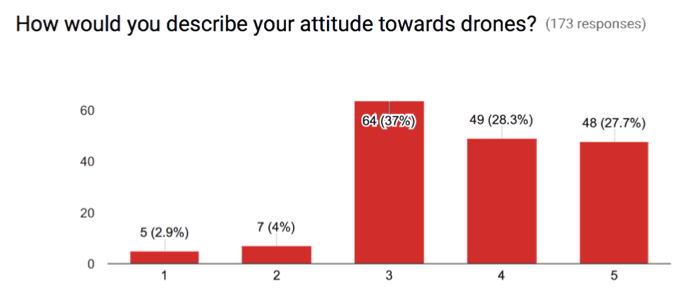

We were not sure what to expect of the polling results. We didn’t know if some students even knew what a drone was. Along with the help of social media and texting, the polling took in 173 responses from students and other Utahns on and off campus in just three weeks. The twelve questions asked in the poll gave us some not-so surprising and some very surprising answers.

One of our most surprising poll results was participants’ attitudes towards drones on a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 being the most positive. We expected to have most people favor the ends: people either having a complete negative opinion about drones, or a complete positive opinion. The result turned out sharply unimodal at 3, the neutral opinion, with almost no responses for 1 and 2. Only 12 out of the 173 responses had negative attitudes for drones (1 or 2), 64 responses had a neutral opinion (3), and 97 responses had a positive opinion (4 or 5). The average response given was a 3.74 out of 5, w hich we like to say is neutral but still positive.

hich we like to say is neutral but still positive.

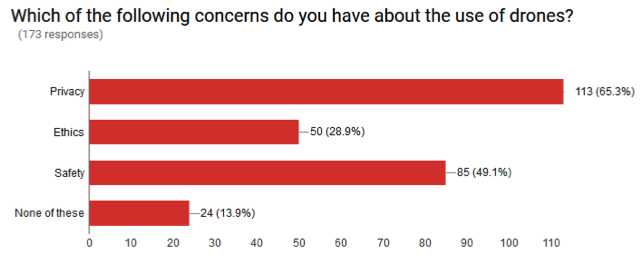

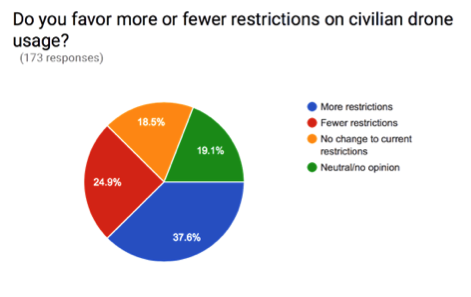

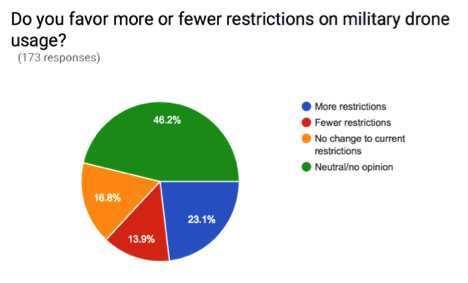

Other polling questions such as “Have you heard the term ‘Drone’ before today?” gave us results that we expected. 100% of responders knew what a drone was. Concerns about drone use were pretty common as well. Of the 173 responses, privacy and safety showed the greatest concern over ethics and none of the above/other, just as we would have thought. The 4 most typical, most heard of, and most popular uses of drones were filmmaking, military surveillance, military attacks, and delivery of products. From the people we polled, more results showed that more than half of people knew a friend or family member that uses drones, a little less than a third had flown a drone before, and only 15% own a drone themselves. Of the people that did own a drone, DJI and GoPro were the most popular brands. Most people used their drones for photography, videography, and just plain recreation.

What we had found the most interesting however, were the restriction opinions about drones. When it came to military drone restriction, about 46% of pollers chose no opinion, 23% chose more restrictions, 17% chose no change, and 14% chose fewer restrictions. On the other hand, pollers had stricter views on civilian drone use. About 38% of pollers favored more restriction on civilian drone use. That’s 15% higher than the results from military restriction. As well, more people had an opinion for the civilian drone use compared to military use. Only 19% chose no opinion in the civilian restriction category, about 27% less than the military category. This could be caused by less general knowledge about military drones then the average GoPro carrying quadcopter. Obviously not a coincidence. Also we found a correlation between owning a drone and what type of restriction you wanted. For the people that owned drones, 60% voted they wanted fewer restrictions, and for people who didn’t own a drone, 65% voted for more restrictions.

Interviews

While the polls were going, twelve interviews took place on the University of Utah campus. After transcribing the scripts from the interviews, the team analyzed the script and here are the results:

First Thoughts

One of the most interesting responses that the group saw was when the question ‘what do you think of when you hear the word drone?’ was asked to the twelve participants. What was clearly evident after looking at only a few interviews is that most people think of different things when they hear the word “drone.” Out of the twelve participants that were interviewed, five of them stated that they first think of video and photography when it comes to drones. They brought up how drones can take videos and pictures and can be used by filmmakers to get different types of videos with unique angles. Also, even though the twelve participants knew what a drone was, many people did not actually understand what they are used for. People stated that when they think of drones they think of ‘little machines that fly’, ‘little toys that fly in the sky’, and ‘me outside in the field messing with people’. As for the other responses by our participants, most people stated that they thought of military drones when they thought of drones.

Military Use

The opinion of how to use drones for military purposes was something that most people generally seemed to agree with. Every person that was asked if drones should be used in the military said that they should be used at least a little bit. Although, most people have heard through the news stories about the stories of drones shooting at civilians and that is why many people stated that the government needs to regulate the military use of drones more. One line that happened to stand out from the rest was one stated by Peter Forsling, a Computer Science major at the University of Utah. When Peter was asked if drones should be used in military use, he agreed that drones should be used and backed it up by saying ‘drones they do have their advantages and we need advantages’. This seemed to be the belief of most of the people that responded to the military side of drones. Even though, people admitted that drones make errors, they understood that drones must used in military combat because the military needs all of the advantages it can get.

Privacy

Another large topic of conversation seemed to be the privacy side of drones in America. With the constant debate of the interpretation of the 4th Amendment with the use of drones, our participants had different responses for the ways drones can be used in when it came to surveillance. When the participants were asked how they would feel if a drone was doing surveillance on their house, responses varied from “I would take that as a compliment” to ‘it scares the heck out of me’. It became clear very fast that people had completely different mindsets on the issue even though almost all of them had the same opinion about drone use in the military. Some people stated that there should be laws for how low drones can fly, while others stated there should be laws for how high drones can fly. Also, a lot of people said that drones should be allowed to survey a house but when asked if they would be okay if a drone surveyed their own house, a lot of them said they would not be okay with that. The conflicting responses that people said with drone surveying explains why the issue is so complicated in America in 2016.

Commercial Use